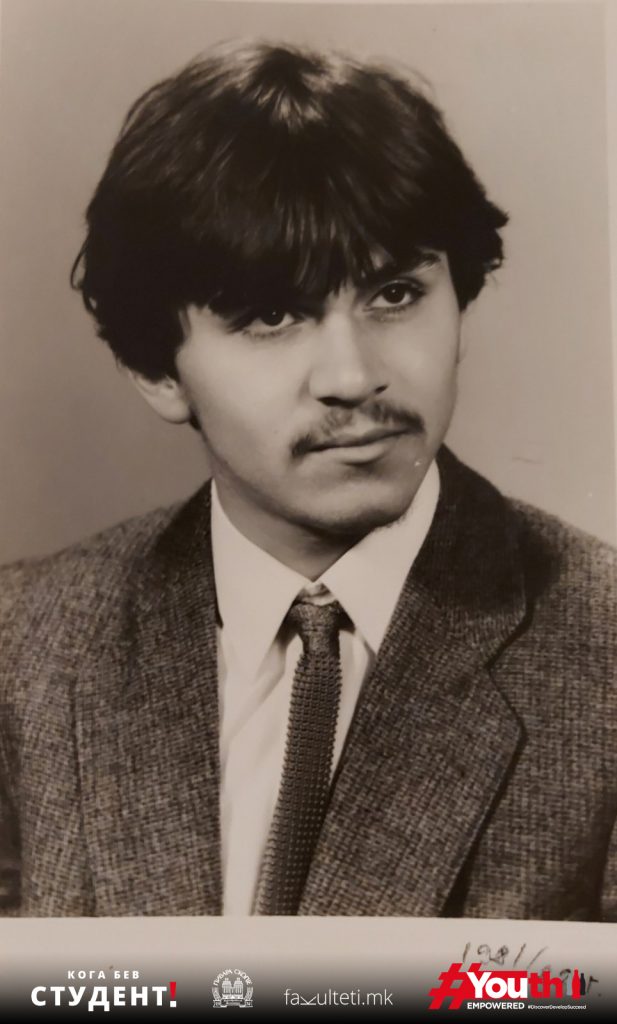

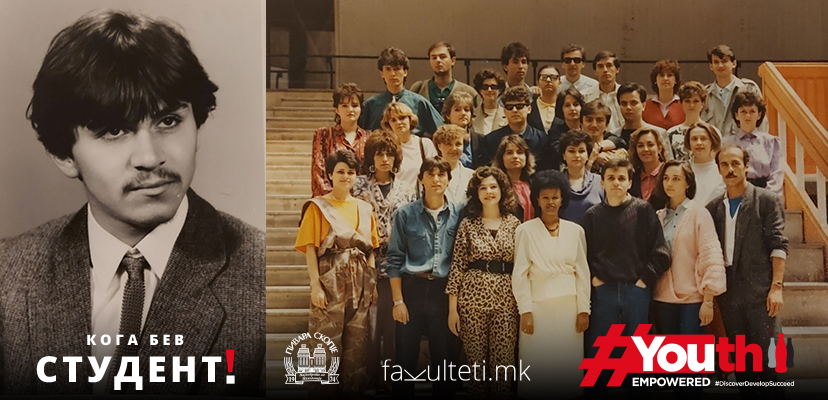

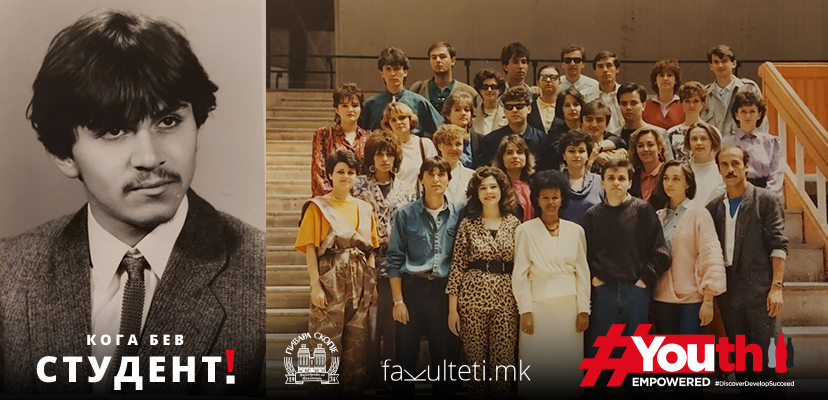

WHEN I WAS A STUDENT WITH GORAN MIHAJLOVSKI: AFTER MORE THAN 35 YEARS I HAVE THE SAME PASSION FOR JOURNALISM AS WHEN I WAS A STUDENT

“As a correspondent for the paper Mladost from Belgrade, I was publishing articles about the first private parties when clubs were being bought out, tickets were being given out, and the Skopje elite was setting itself apart… I was also reporting from the concert of the band Videosex with Anja Rupel. I told the photographer not to come with me, that I’d take the photos myself, so I’d get a chance to get close to Rupel, I liked her a lot,” Mihajlovski tells us, laughing, describing his student experience to the column that Pivara Skopje publishes together with Pivara Skopje fakulteti.mk

From a young age he loved to travel, but also to write, so journalism was a good combination of the two. Even after more than 35 years in the profession, Goran Mihajlovski has the same passion for journalism as when he was a student. He started out at Student Word, where he got to the position of deputy editor-in-chief and where he learned the most about journalism, and then went on to the Vecher newsroom. He reached the pinnacle of his career at Vest, and in the last four years he and his team have been creating the portal sakamdakazham.mk.

A combination of writing and travel

Mihajlovski says he chose journalism not because he liked it so much, but because it seemed as an enticing profession because he couldn’t see himself trapped in an office. He enrolled in journalism studies in Skopje in 1982. Immediately after enrollment, he had to leave for Belgrade to serve in the military.

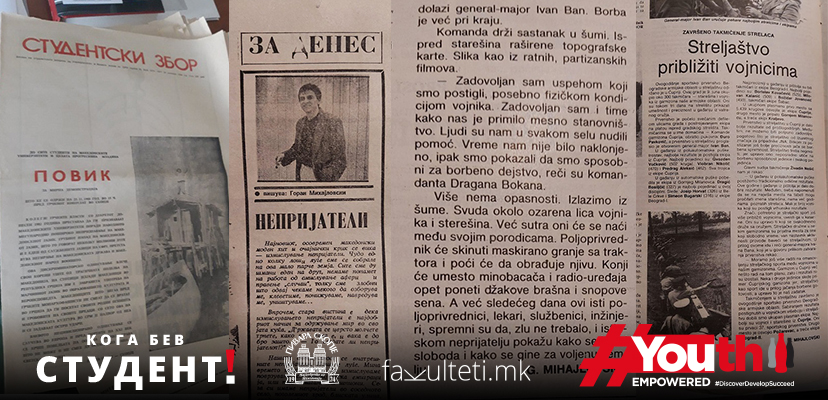

“After my military training, I worked on the editorial staff of the biweekly Soldier, the official newsletter of the then YNA Belgrade army area. It was there that I first smelled the scent of the printing press. The magazine was being printed in Borba’s printing house and we had to go keep watch. One day my uncle Lambe Mihajlovski, who was a general in the then YNA, came to visit the editorial office. He pulled me out of the barracks and took me to a specialized store in downtown Belgrade, where he bought me my first typewriter. I keep that typewriter in my newsroom as an ornament now. When I came back to Skopje, I started working part-time at the then Student Word in parallel with my studies, and found my way quickly. I started with dorm stories, and by the end of my studies I’d reached the position of deputy editor-in-chief and was writing political editorials. I learned more about journalism at Student Word than I ever did in class,” says Mihajlovski.

His family supported his choice of study. He says: “My brother (actor Jovica Mihajlovski) ‘paved the way’ for me by changing two majors before he found himself at FDU.” So his parents did not want to make the same mistake with Goran – to impose on him a choice of study as they had done with Jovica – and resigned themselves to the fact that he would study to become a journalist.

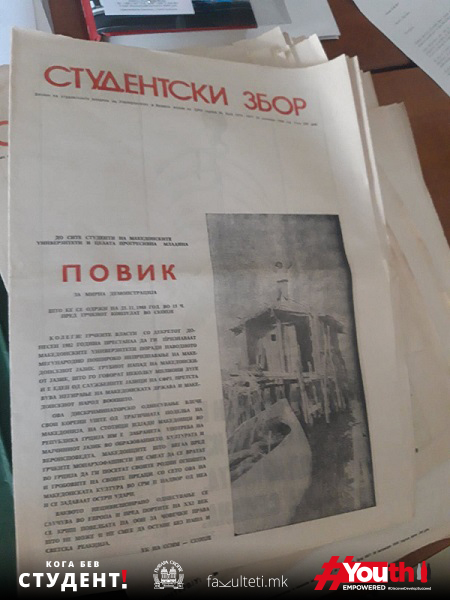

Student Word – a real school of journalism

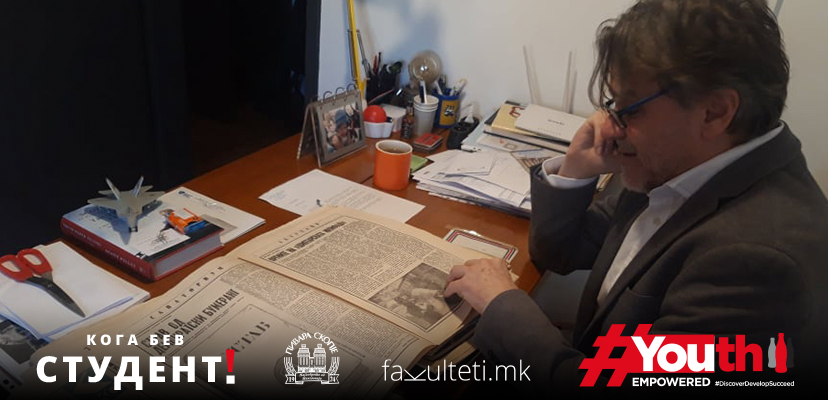

He got the knack for journalism quickly. Student Word was being printed in Nova Makedonija’s printing house. Printing watch shifts were then mandatory for journalists, the final signoff before a paper came out of the presses had to be done by an on-duty journalist, and Mihajlovski is nostalgic about those days. He says: “I miss the smell of the printing press.”

“Student Word was an editorial staff with all the bells and whistles – journalists who wrote about politics, about students, about culture, a true staff of about a dozen people. Biljana Sekulovska, Zoran Kostov, Zhaneta Skerlev, Mice Jankuloski, Tome Gruevski who was first an editor and then became director of Student Word – all of them were on the team. We had more freedom to write than the ‘serious media’ did. We covered topics on the student standard of living, we did reportages on the dormitories, we published interviews with politicians. Everything that was being interpreted as a liberal attitude at the time could be found in Student Word. We received some monthly honoraria, business travel expenses, so at the time we were living comfortably for university students, we didn’t have to ask our parents for money for drinks, we could go out with our own money, and even saved up for a little vacation here and there. At the time, my brother and I were sharing an old Fiat 500, so those honoraria were just enough for me to fill it up with gas instead of taking the bus,” Mihajlovski recalls.

During his studies, in 1986, at the faculty, outside of Student Word, journalism students released a fanzine called Phoenix, of which only two editions were published. He recalls them running into a huge problem when they published an interview with Kole Chashule titled “People who had two Ilindens will have a third”.

“On the cover with that headline we put a photo of a man who was missing a leg, alluding to Tito. The next day, all of us who were listed as members of the editorial staff were called in by the police, and one by one we were brough in to UDBA for questioning. I remember that the editorial staff at the time included Vitomir Dolinski, Zoran Dimitrovski, Marina Kostova, Valentina Velevska (now deceased), and we were telling each other how we’d done with the police,” laughs the editor-in-chief of sakamdakazham.com.

Another youth magazine at the time was Young Fighter, whose editor was Nikola Mladenov, the founder of Fokus. Goran and Nikola went to the Nikola Karev Gymnasium together. Although not competition in terms of the current type of market competition, Goran admits that Nikola Mladenov at the time was making a much more liberal and bolder youth newspaper.

The Faculty of Philology cafeteria – a favorite spot

He and his fellow students hung out a lot, and some of those friendships are still nurtured today. Goran and Biljana Sekulovska meet sdaily; Marina Kostova is the deputy editor-in-chief of the digital editorial board of sakamdakazham.mk.

“With Jugoslava Dukovska, Gordana Duvnjak, Santa Argirova, Emilija Lazarevska, Jugoslav Kostovski, Toni Zografski, Aleksandar Muchev, Silvana Brkuljan I hang out from time to time at reunions. Once a year we have dinner in honor of our late colleague and friend Julijana Nedelkovska, who used to initiate such meetings,” says Mihajlovski.

They were all good students, a compact group of about two dozen people, and functioned as a high school class.

“Since we were in interdisciplinary studies, we had classes at all the faculties and most often gathered at the Faculty of Philology, which had the best cafeteria. In the evenings we went out to Musandra, Hearth, private clubhouses, 63 at Bit-pazar, Alpino by the Green Market, drove to some parties on Teferich, to the then Panorama Hotel or Treska Lake. In the summertime we’d go to England to do seasonal work. Several people in our year used to work illegally in London. At the time it was simple to do so with a Yugoslav passport, they didn’t require visas,” says Goran.

As for studying, Goran says he tried to get good grades, but he never re-took an exam for a higher grade average.

“I think Professor Denko Maleski went easy on me. He told me, ‘This is your grade as if you’re a figure skating – you get a 5 as your technical mark and 10 for artistic impression, so here’s a 7.’ I failed Dimitar Micajkov’s class a hundred times, like all my fellow students did. The Macedonian language course was the most boring one for me. I didn’t want to study because there was too much theory. We took written and oral exams. I remember that in sophomore year, I and my fellow student Mejrem Sali, who is a journalist in Turkey, instead of studying, spent more time making cheat sheets. But we failed to use them and eventually shamelessly pulled out our notes, because the exam was in a big amphitheater. The time came for us to take the oral exam. The professor sat us both down and gave us something ridiculously easy to translate from Serbian into Macedonian, just to play a joke on us, and said, ‘Bravo, you did well!’ And gave us a huge 5. He added: ‘Are you not ashamed? You cheated, but you copied the wrong chapter!'” our interlocutor laughs.

Going to Marjanovic’s lectures even though we weren’t taking his course

It was very interesting and easy for him to pass exams with professors Tomislav Chokrevski, Nikola Kljusev, Taki Fiti, etc. He and his fellow students would attend the lectures of Gjorgje Marjanovic, and although he did not teach journalists, but only lawyers, they wanted to listen to him because he taught very interestingly.

“We all wanted to listen to Professor Marjanovic’s fun lectures,” recalls Mihajlovski, adding a few more professors whose lectures he gladly attended as they were free to discuss – Dimitar Mirchev, Ferid Muhic, Kiril Temkov, Denko Maleski…

While he was studying, he knew that he needed to do it only to get a degree, because journalism is best learned in a newsroom. Paradoxically, they learned the most about how to write a news article in the English course taught by prof. Zoran Anchevski.

“He brought us journalism books from England and we actually learned how to write news in English. And we learned more about journalism through that course. Many of my fellow students were working in the media while studying, doors were opened everywhere for us. Journalism isn’t something to be learned from a book alone. Journalism is learned when you feel the pressure, when time is pressing because there’s a deadline, when you’re rushing to be the first to publish something, when you’re struggling to get a statement, to go to the field… For example, I as a child who grew up in Skopje, had I not been a Student Word journalist, would never have had the chance to see how students from other places lived. So I met many students who lived in dormitories or private apartments. For example, I interviewed the then-student activist Gjulistana Markovska at the Goce Delchev dorm. We were freezing because the heating was out. She’s now a doctor, and she also used to be an MP,” Mihajlovski recalls.

Students’ struggles at the time were similar to today’s. Goran tells the story of being sent to report on how future doctors were living in the barracks at the then Medicinar dormitory. The report was supposed to be inspiring because medical studies are among the hardest. Instead of a positive report, Goran came back to the newsroom stunned.

“I remember doing two or three follow-ups with horrible pictures of the barracks and immediately afterwards students called me to continue the story with the Stiv Naumov student dorm. It was even worse there,” says Mihajlovski.

He does not know if these reports changed anything, but he remembers that he was then tasked with reporting on the student dormitory in Bitola in order to correct the impression.

“I went to Bitola, I did the reportage. The rooms were nice, the Bitola University was new at the time, and the dorm was tidy,” says Goran, who to this day feels good if his journalism helps someone or at least initiates a change.

Vecher – his first professional job

Mihajlovski tried to work in television for a short time, but quickly realized that it was not his medium. He was part of the team of the show Hello, Youth on TV Skopje, along with Katerina Blazhevska, Santa Argirova, Zoran Dimitrovski, and their editor was Ivan Andreevski.

“We were covering youth topics, in principle we had a lot of freedom and the show was a breath of fresh air on the air. Then it had it very easy when I got my first professional job at Vecher in 1989, which was a much more liberal newspaper than Nova Makedonija. I was lucky that my editor-in-chief was Zlatko Blajer and his deputy was Aleksandar Ivanovski. They were very liberal and I came in as a fresh force. My first big task was when I was sent to report from the Youth Congress in Portoroz, Slovenia, which was the announcement of the breakup of Yugoslavia,” Mihajlovski recalls.

“I remember once writing an article with a dramatic headline – ‘GEKA versus CEKA’, because the then City Committee was quarreling with the Central Committee. Such a headline was unusual at the time. The editors hesitated at first, but kept the headline, and there were many reactions,” he says.

The editor-in-chief of sakamdakazham.mk admits that he can cover any subject, but just does not feel competent to write about culture and art. He says he was also part of the team that produced the newsletter at the beginning of the Skopje Jazz Festival in 1983.

“As a student, it was fun for me because I was also covering entertainment events as a correspondent for the Mladost paper from Belgrade. I was publishing articles about the first private parties when clubs were being bought out, tickets were being given out, and the Skopje elite was setting itself apart, who could get in and who couldn’t… I was reporting from an Idoli concert that went very poorly because the sound system in the Rabotnichki arena gave out. I was also reporting on a concert by the group Videosex with Anja Rupel at Youth House 25 May (today’s MKC). I told the photographer not to come with me, that I’d take the photos myself, so I’d get a chance to get close to Rupel, I liked her a lot,” Goran recalls.

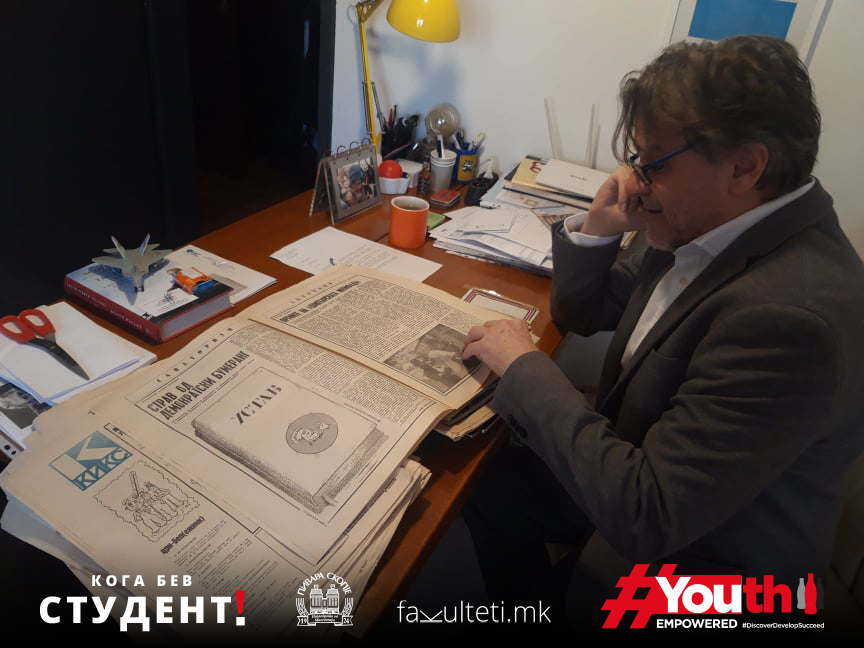

After graduating, he was the editor-in-chief of the in-flight magazine of the first Macedonian airline Palair Macedonia, which was being published in three languages: Macedonian, Albanian and English. He’s had a passion for planes ever since – his office looks more like a travel agency that an editor’s office with the two dozen model airplanes.

Most grateful to Zlatko Blajer and Aleksandar Ivanovski

He is especially grateful to editors Aleksandar Ivanovski and Zlatko Blajer for the knowledge they imparted and the chance they gave him in Vecher. Blajer recognized his potential and gave him contentious topics, while Ivanovski was the man who in a way discovered the “I Want to Say” (“Sakam da kazham”) column, first published on January 12, 1991.

“He liked my writing. He once tasked me with writing commentary on Saturday, then the Saturday after that, then the Saturday after that, so it turned out that I had to write it every Saturday, even though I didn’t always have anything to say. The name “I Want to Say” came very spontaneously, because I was using that sentence in my writing,” Mihajlovski recalls.

For several years, Mihajlovski taught Media Editing at the Faculty of Journalism in Skopje.

“I love working with young people, you always learn from younger people. However, frankly, I was devastated by the laid-back attitude with which the students treated journalism and their general illiteracy. They said to me, ‘Well, Professor, we aren’t studying to become proofreaders, we’re studying to become journalists.’ What am I supposed to do with them? Fail them, when they’ve already reached junior year? It’s devastating and unfortunately it’s already being seen in the media.”

Mihajlovski says the only crisis in his more than 30-year journalistic career was at the time when the German media company WAZ, which also owned Vest, sold its newspapers.

“Both as editor-in-chief and as a journalist, it was very difficult to maintain professional integrity. Who knows when journalism will recover entirely,” says Mihajlovski.

He says he still has a great zest for journalism, that he still has enthusiasm and has no problem running to the scene when something major happens.

“When the accident in Laskarci happened, because I live the closest, I ran to September 8, I stopped in front of the ER, took pictures, asked around, sent pictures to my on-duty colleagues. On another occasion, there was a nighttime shooting between two gangs near my home. I was out and without thinking, I called my underage children to go outide, see what had happened, and send me photos to post quickly. Can you imagine my wife’s reaction?” Mihajlovski laughs.

He says he finds his subject matters in everyday hangouts and at various events. He spends his free time with friends whose professions have nothing to do with journalism. He says it relaxes him, even though there is no such thing as being off-duty for a real journalist. Very often big topics have come out of conversations with them while out for a drink and hanging out.

“People can’t tell whether what they’re telling me is newsworthy or not. That’s my job,” says Mihajlovski.